FOR A FEW DAYS IN APRIL, a grocery store chain in New England magnetically attracted Democratic presidential hopefuls. Thousands of Stop & Shop workers were on strike in the biggest private-sector walkout in years. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (Mass.), Mayor Pete Buttigieg (South Bend, Ind.), former Vice President Joe Biden and Sen. Amy Klobuchar (Minn.) all joined picket lines to stand in solidarity. Others tweeted messages of support.

“This is morally wrong what’s going on in this country, and I’ve had enough of it,” Biden said. “I’m sick of it, and so are you. We gotta stand together, and if we do, we will take back this country—I mean it.”

By May, the labor conflict making headlines was McDonald’s workers striking for a $15 wage. Sen. Kamala Harris (Calif.), former U.S. Housing Secretary Julián Castro, Mayor Bill de Blasio (New York City), Sen. Bernie Sanders (Vt.) and Gov. Jay Inslee (Wash.) joined street protests. Nearly a dozen others expressed support for workers.

“We have got to recognize that working people deserve livable wages,” Harris said, noting she once worked at McDonald’s.

During the primaries, Democratic presidential candidates have always made a point of showing up at union halls and playing up ties to working people: It’s one of the first pages in the Democratic political playbook. Biden officially started his campaign at a Teamsters banquet hall in Pittsburgh, announcing he is a “union man.” Warren kicked off her campaign at the site of the historic 1912 textile workers’ Bread and Roses strike in Lawrence, Mass. Klobuchar and Sen. Cory Booker (N.J.) mention union members in their extended family while speaking to union audiences.

The next by-the-book move is a pivot to the center during the general election. After fighting for union endorsements during primary season, the Democratic nominee zeroes in on swing voters, taking union voters for granted even as unions send a door-to-door army to get out the vote. Labor has been a core part of the Democratic Party’s coalition going back to the Great Depression.

Eighty years later, in 2016, something changed. Donald Trump had the best GOP presidential candidate performance with union households since 1984, trailing Hillary Clinton by only 8 percentage points. In 2012, Mitt Romney trailed Barack Obama in this demographic by 18 points. All of which raises the question: Are Democrats losing labor as a reliable constituency? Dems can still count on union endorsements, to be sure. But with Trump attacking from the left on free trade, support from white male union members—who still make up a plurality of the movement’s members—is up for grabs.

This uncertainty was born of neglect: Since the 1970s, as the country’s industrial base withered and unionbusting flourished, Democrats in Washington have done little to reverse the labor movement’s decline. Under Presidents Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, union money and organizing muscle helped deliver control of Congress and the White House to Democrats. Each time, the party failed to pass labor law reform that would have empowered workers and bolstered the movement.

In 2016, the party paid an electoral price for their waywardness. This time around, will candidates do more than pander during the primaries? Public support for labor is at a 15-year high, especially among young people, women and college graduates. Nearly half a million workers were part of a strike or lockout last year—the highest figure since 1986. Might we finally see Democrats place unions at the heart of their political agenda? It’s far-fetched, but conceivable. Candidates know they can no longer take union votes for granted.

More significantly, the center of gravity on labor and economic issues has moved left.

“There’s this sense now that we have a big problem of inequality and capitalism run amok,” says Nelson Lichtenstein, a history professor at University of California, Santa Barbara, where he directs the Center for the Study of Work, Labor and Democracy. “That’s clear on the Democratic side. But what is the solution? Is it about taxation? Or is it vitalization of the union movement? That latter idea has become more understood.”

In some ways, candidates’ rush to the left makes it harder to discern just how deeply committed they are to strengthening unions. Everyone always says they want to rebuild the middle class. Who really wants to rebuild the labor movement?

RAISING THE BAR

If you zero in on the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) ACT, the answer appears to be: most of the leading candidates. Co-sponsored by 40 senators and 100 members of the House, the PRO Act offers a litany of labor law reforms. The larger context here is that the United States has among the weakest workers’ rights protections of any industrialized country—on par with Myanmar, Pakistan and Ethiopia. Over the past 40 years, employers have aggressively fought unionization through (perfectly legal) tactics like “captive audience” meetings, when workers must sit and listen to anti-union presentations, or the (sometimes legal) firing of striking workers.

The PRO Act would strengthen the right to organize and strike by, among other things, eliminating so-called right-to-work laws, banning permanent strike replacements, legalizing secondary boycotts and picketing, and broadening the definition of “employee” to include many current independent contractors. Compared to the Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA), the reform law pushed by the labor movement during the 2008 election cycle that ultimately died in the Senate, the PRO Act is a progressive smorgasbord. But the PRO Act does fall short of EFCA in one significant regard: While EFCA enabled workers to organize through a majority sign-up process (“card check”), the PRO Act only requires card check if an employer is found to have violated labor law during a failed union election. Every current senator running for president backs the bill.

With multiple leading candidates able to point to a history of support for unions, today’s Democratic field stands in stark contrast to the 2016 primary with its binary choice of establishment liberal Hillary Clinton versus change agent Bernie Sanders. Nearly all unions endorsed Clinton, many early on, rankling rank-and-file Sanders supporters. This time around, unions are in no hurry to back a candidate—only the International Association of Fire Fighters has done so (Biden got the nod). The American Federation of Teachers (AFT), the National Education Association and others have unveiled new endorsement approaches to more deeply engage both candidates and members (and, one assumes, to close any perceived distance between the wishes of the rank-and-file and executive boards).

“There’s intensity for a bunch of candidates this time,” says Randi Weingarten, president of the AFT. The union endorsed Clinton in July 2015 and poured $1.7 million into her campaign and pro-Clinton PACs.

Heartburn from the calamitous 2016 election appears to be giving the union endorsement process a dose of democracy. As millions of union members decide who to back, they’ll be wrestling with the question of which candidate would most effectively fight for their interests. Because the leading Democratic candidates are staking out similar ground to make their case, it’s important to look at the candidates’ records, how central the union movement is to their theory of change, and what unilateral actions they would be willing to embrace as president (should Congress fail to act)

DIFFERENCES BIG AND SMALL

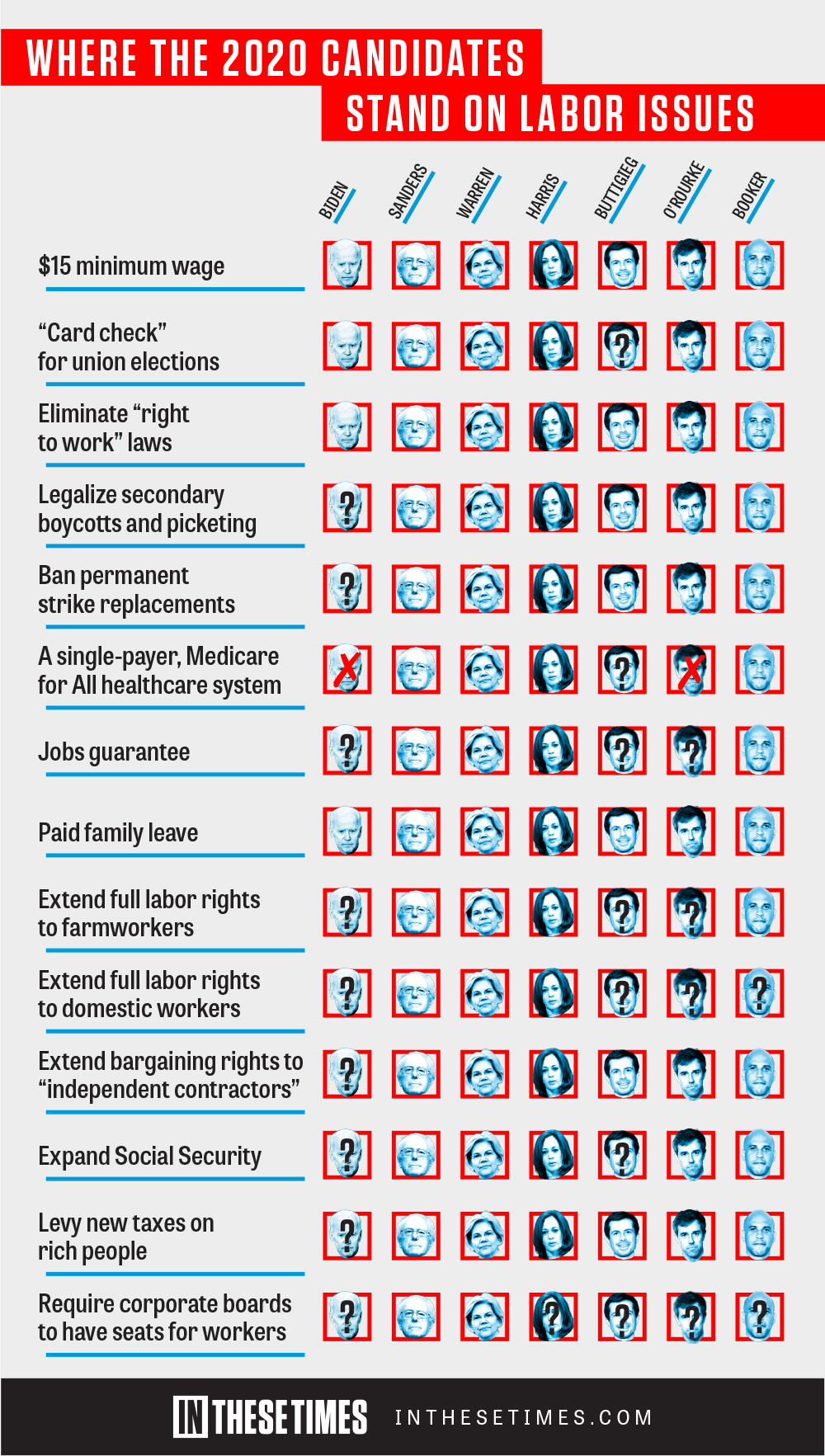

This much is clear across the Democratic primary field: Raising the federal minimum wage to $15 and taxing the rich have become table stakes. All the leading candidates—Biden, Booker, Buttigieg, Harris, former Rep. Beto O’Rourke (Texas), Sanders, Warren—support both. Beyond those two issues, the top of the field is replete with differences big and small.

It’s easy to sort out where candidates stand on a raft of proposed legislation. It’s harder to know what they would try to do for the labor movement if all those proposals become moot—which will be the case should the GOP hold the Senate.

Biden is an old pro at signaling he’s a fighter for the union cause, but it’s hard to find an example of him sticking his neck out for workers. In May, Biden held a fundraiser at the Los Angeles home of a board member of Kaiser Foundation Hospitals, a subsidiary of healthcare giant Kaiser Permanente. The National Union of Healthcare Workers (NUHW), which has a longstanding dispute with Kaiser in California over mental health staffing levels, called on Biden to cancel the event. They never heard back, says NUHW President Sal Rosselli. NUHW members protested outside the house, but Biden “went into the event and didn’t even talk to our folks,” Rosselli says. “That’s very disappointing.”

Biden also didn’t endear himself to the labor movement by voting for NAFTA and supporting the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement, both of which unions opposed. Biden did support EFCA as a senator but has not committed to the PRO Act, and his campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

In contrast, the leading presidential candidates from the Senate have been out front on labor law reform. Sanders has been pushing the Workplace Democracy Act (WDA) for decades (beginning as a congressman in 1992), which is co-sponsored by Booker, Harris and Warren. The WDA can be seen as a forerunner of the PRO Act; it also legalizes secondary boycotting, stops companies from delaying a first contract with workers and gives bargaining rights to many workers who are currently classified as independent contractors. (Unlike the PRO Act, it would let all workers unionize via card check as a matter of course.) Sanders’ method has been persistence: He reintroduced the WDA throughout the 1990s in the House, then brought new versions into the Senate in 2015 and 2018. As with other issues, such as Medicare for All, the Democratic Party has now caught up to him.

It took Sanders years to earn the backing of any national union. They didn’t flock to him when he first ran for Congress in 1988, but came around after he won congressional campaigns in the early 1990s. Today, Sanders remains as outspoken as ever about the power of unions—they live at the heart of his agenda. “The trade union movement is the last line of defense against a corporate agenda that not only wants tax breaks for billionaires but wants to privatize Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid,” Sanders told In These Times via email. “We must strengthen unions and bargaining rights of workers everywhere.”

It’s not hard to imagine the other leading candidates saying something similar—indeed, most have before crowds of union members. It’s Sanders’ long record of actually supporting labor actions that makes him stand out. Political candidates love to call their campaigns a “movement,” and Sanders is no exception, but it feels less cliched when a campaign actively urges supporters to join protests around the country—like those held by University of California campus workers and Delta Air Lines flight attendants. “What Bernie is doing is very, very unique,” Lichtenstein says. “The most radical thing in this campaign cycle that’s happened is Bernie using his email list to get people to picket lines and protests.”

In March, Sanders’ staffers became the first presidential campaign staff to unionize, starting a trend. Castro’s campaign staff followed in May, and Warren’s team did so in June. The candidates each publicly supported the union efforts. “Every worker who wants to join a union, bargain collectively, & make their voice heard should have a chance to do so,” Warren tweeted.

Unlike Sanders, Warren can’t point to decades of direct solidarity work with the labor movement, but the two New England senators share much in common. Yes, Warren has called herself “capitalist to my bones” while Sanders keeps trumpeting his democratic socialism, but both have New Deal liberalism deep in their blood—including the sense that worker empowerment is vital to economic justice—and they broadly agree that American capitalism needs structural change.

Warren’s Accountable Capitalism Act is a good example. Introduced in the Senate in 2018, the bill would empower employees to elect at least 40% of board members at large U.S. companies. This new board could then (in theory) push management to do something about yawning pay disparities between the C-suite and average workers. For Sanders’ part, he unveiled plans in May to boost employee ownership of corporations and attended a Walmart shareholders meeting in June at the request of United for Respect, a workers’ rights group, to support a resolution to require Walmart to put hourly employees on its board.

Both senators want to do more than tinker around the edges of neoliberalism. This perspective, and a willingness to call out the rich as an enemy along class lines, is what sets them apart from their primary season peers.

“Strengthening America’s labor unions will be a central goal of my administration,” Warren told In These Times via email. “For too long, a worker’s right to unionize has been under attack. The rich and powerful have teamed up with the Republican Party to push for measures at all levels of government designed to decimate unions and collective bargaining.”

Warren says she wants to “modernize our labor laws for the 21st century,” noting various reforms included in the PRO Act, and that she would fight for “fully portable benefits for everyone and make sure that all work—full-time, part-time, gig—carries basic, pro-rata benefits.” She also wants to push to amend federal law so the president and federal courts cannot “enjoin lawful strikes that pose a threat to national health or safety.”

“Far too often, these injunctions have been invoked in strikes not because there is a genuine threat to national health or safety, but rather to curb the power of unions engaging in lawful strikes,” she says.

This attitude has endeared Warren to the labor movement. She spoke in Las Vegas at the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and Center for American Progress Action Fund’s National Forum on Wages and Working People in April, along with a handful of other candidates. “We need more power in the hands of employees,” she said. The Washington Post reported the crowd gave her its “most passionate response.”

THE REST OF THE FIELD

To be sure, other leading candidates have built up support within the labor movement. Buttigieg, for example, has been in tune with the building trades unions in South Bend. “He’s been fantastic,” says Jim Gardner, business representative of the Operating Engineers Local 150. Buttigieg spoke out against repealing the common construction wage and backed a “responsible bidding” city ordinance that requires any company bidding on a city contract to reveal OSHA violations, Gardner says. Buttigieg’s unsuccessful 2010 campaign for Indiana state treasurer was run from the building trades office in South Bend, says Mike Compton, who was business manager with IBEW Local 153 until 2016. “Pete did what he could for us and with us,” he says.

Buttigieg tells In These Times, “I believe that unions must have a powerful seat at the table—to stand up against unfair and abusive practices and to collaborate in improving work environments and productivity.”

With no offense to South Bend, Harris’ deep ties to California unions could prove a bit more valuable come Super Tuesday. The state’s biggest unions backed her 2016 campaign for Senate and the former president of SEIU California, Laphonza Butler, is one of her top strategists. “We’ve known Kamala since she first ran for district attorney in San Francisco, and we have supported her and endorsed her ever since,” NUHW’s Rosselli says. “She’s extremely responsive to workers’ issues, union issues.”

In May, Harris unveiled a gender pay equity proposal that would require companies to seek “equal pay certification.” Companies would be fined 1% of their profits for every 1% wage gap that persists between men and women. Harris has also championed measures to extend full labor rights to domestic workers and farmworkers, two groups excluded from the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (in a racist compromise with Southern lawmakers). And she has proposed the largest-ever federal investment in teacher pay: $300 billion over 10 years to boost teacher salaries by an average of $13,500.

As likely intended, the plan piqued the interest of at least one rank-and-file teacher, Lucy Moreno. An elementary school teacher and AFT member in Houston, Moreno frequently spends money out of pocket on school supplies. “We teachers are at our breaking point,” Moreno says. Most of the issues that will be top of mind for her this primary season hook to education—better pay, less testing and student loan forgiveness.

Moreno also liked what she heard from Biden in May at an AFT-sponsored town hall event. She says she has not been following the campaign of O’Rourke, the leading candidate from Texas.

O’Rourke’s relationship to unions has had a few bumps. He didn’t endear himself to the Texas AFL-CIO after failing to attend its January 2018 convention during his challenge to Republican Sen. Ted Cruz, but ultimately won the endorsement. And as Vox has reported, O’Rourke’s voting record in Congress was more conservative than the average Democrat’s. He has backed easing regulations on Wall Street and raising the eligibility age for Social Security.

Booker’s current stance on labor and workers’ rights is solidly progressive (relative to the other leading candidates), but he has a bit of an Achilles’ heel: his longstanding support for school vouchers and the charter school movement in Newark, N.J., where he was a city council member and mayor. Along with Republican Gov. Chris Christie, Booker wanted to make the city “the charter school capital of the nation.” Newark teachers unions were less enthused with the plan—and teachers nationwide may prove less than enthusiastic with Booker’s candidacy, given their growing willingness to strike.

The issue isn’t just Booker’s “school reform” past, but the way it illuminates his neoliberal tendencies. In a 2011 speech at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, he said that “disparities in income in America are not because of some ‘greedy capitalist’—no! It’s because of a failing education system.”

Of the candidates polling at 2% or less as of early July, none emerge as a “labor candidate.” Rep. Tim Ryan (Ohio), a long-time magnet for union donations, touts his Rust Belt credentials and says he was spurred to run by the closure of the Lordstown General Motors plant in his district. But Ryan’s stump speech rarely includes the phrase “union jobs.” He focuses on the need to invest in electric carmaking. Conversely, Inslee, more known as a “climate candidate,” has made unions and a job guarantee central to his climate plan.

Serial entrepreneur Andrew Yang is running as a capitalist who saw the light on economic inequality and the threat of automation. His trademark proposal is a guaranteed universal income of $1,000 a month that he calls a “freedom dividend.” In a 2018 Labor Day blog post, Yang gave the impression of having recently discovered U.S. labor history, enthusiastically relating the life story of Walter Reuther. He closed with an appeal to unions to support his freedom dividend, noting: “It would also dramatically increase worker bargaining power, as workers would have a cushion to fall back on and could push harder against exploitative labor conditions.”

Klobuchar never misses an opportunity to mention she is the granddaughter of a union miner and daughter of a union teacher and a union “newspaper man.” The line drew weak applause from union workers in March at the SEIU labor forum in Nevada, compared to cheers for Warren’s policy proposals. Klobuchar has also had to contend with reports of emotionally abusive behavior toward her staff.

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (N.Y.), historically a centrist, has run hard to the left and brings up labor proposals, unasked, in interviews, including debt-free college, a Green New Deal, affordable day care, a national paid leave plan and equal pay. Her most noteworthy position may be full employment, which she tells Splinter News she will effect through “apprenticeship programs, not-for-profits, and community colleges to train local workers for real, available, good-paying jobs.

EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONING

Presidential candidates always focus on legislation as a way of defining their values and political program, and a lot of them this cycle would do a lot of good for workers—from various tax plans to the PRO Act to the Family Act (introduced by Gillibrand in February, it would mandate up to 12 weeks of partially paid leave for various health reasons). But all of it will come to naught if the GOP holds the Senate, and even if Democrats gain the majority, don’t hold your breath: Pro-business Democrats couldn’t stomach EFCA in the Senate back when their party controlled all of Congress in 2009, so they will likely be happy to obstruct the far more expansive PRO Act.

Larry Cohen, former president of the Communication Workers of America, notes that the filibuster, which requires 60 votes to overcome, prevented EFCA from passing and watered down the Affordable Care Act.

“Are [candidates] prepared to work to change the way the U.S. Senate operates, should we be lucky enough to get 50 Democratic senators again?” asks Cohen, who is now board chair of Our Revolution, the organization that emerged from the 2016 Sanders campaign.

Warren, Buttigieg and O’Rourke are in favor of eliminating the filibuster. Sanders, Harris and Booker have vacillated but are leaning toward the status quo. Biden, who spent 45 years in the Senate, tends to defend the chamber’s traditions. He has spoken in favor of the filibuster, although not this year.

Nonetheless, given the likelihood of a divided government (or a divided party), the leading Dems are strikingly silent about how they might directly wield the Oval Office to bolster the labor movement.

A president can do plenty to drive a pro-labor agenda through the federal government without Congress, such as make strong appointments to run the Department of Labor (DOL) and sit on the National Labor Relations Board, says Moshe Marvit, a Century Foundation fellow who focuses on labor and employment. Actually enforcing current laws could make a huge difference, too—the DOL could, for example, aggressively bring lawsuits against companies that misclassify workers as contractors, while the IRS could pursue the same bad actors for tax evasion, Marvit says. Or the president could bring more people from workers’ rights groups and unions with firsthand knowledge of the challenges into policymaking—a teacher to run the Department of Education, for example. The DOL’s Bureau of Labor Statistics could expand data collection on unfair labor practices, union-busting and other employer violations and sexual harassment in the workplace. And, says Marvit, it could restart its tracking of strikes and walkouts that involve fewer than 1,000 workers, which stopped a few decades ago.

In These Times asked Biden, Booker, Buttigieg, Harris O’Rourke, Sanders and Warren what they would do, legislatively and executively, given the chance. Biden, Booker, and Harris did not respond. Buttigieg and Sanders cited only legislative plans—Buttigieg, for example, wants a new National Labor Relations (Wagner) Act to cover workers historically excluded from collective bargaining, and Sanders wants to pass his Workplace Democracy Act, which includes “the right to know if [a] company spends huge amounts of money to run anti-union campaigns.”

O’Rourke sent a brief response, but a spokesperson expanded on it to say that the candidate would increase employer penalties for interference with worker organizing and increase investments in workers’ rights enforcement mechanisms. (Harris has also pledged to crack down on companies “that cheat their workers,” and Sanders has elsewhere promised to restore the Obama NLRB’s expanded overtime protections.)

Only Warren’s response detailed proposed executive actions, saying she would appoint people “who have a history of fighting for workers and are committed to fighting for workers’ rights” to help lead her administration. She also says she would give union members a “real voice” in trade deal negotiations, reimplement Obama’s overtime pay expansion rules and prevent employers from misclassifying workers as independent contractors. “I will use the White House bully pulpit to support workers,” she says.

Warren’s two-pronged approach is something Marvit would love—a governance approach that places the struggles of workers at the center of public discourse, while making policy changes in the background. Think of it as flipping the Trump script.

“Every president gets to define how they talk about the economy,” Marvit says. “Trump has made it all about trade and tariffs, so suddenly we’re all talking about trade and tariffs in the news every single day. Another president could really frame economic concerns around labor and employment issues. It will force people to choose sides.”

Imagine a president publicly condemning a company for misclassifying workers as contractors, and then harnessing the full range of executive branch powers—the Department of Justice, the Department of Labor, the IRS—to punish bad actors. The scenario can only occur if the president thinks of workers not just as an interest group, but as their core constituency, Marvit says. “There has to be a worker concern in every single policy that is taken, whether you’re talking about healthcare, whether you’re talking about the environment, whether you’re talking about employment.”

Jane McAlevey, a former union organizer and author of No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age, says that getting a sympathetic Democrat in the White House is only the first step. The next, McAlevey says, is a massive wave of strikes.

The relationship between direct action, power and creating a crisis with a Democrat in the White House is “the missing link so often in this discussion,” McAlevey says. The labor movement should back a candidate who will “restore the fundamental constitutional right to strike” (as the PRO Act effectively would) and commit to never calling out federal troops on striking workers. “We need a candidate … who commits to defending the right of workers to be on strike and using the full resources of the federal government to aid workers in re-claiming some of what’s deserved by the working class.”

Nothing like that has been seen in the United States since the 1930s, when FDR first entered the White House and waves of strikes followed. The backdrop was the Great Depression. Short of another crisis, far-reaching strikes are far-fetched. But one thing is clear enough: Waiting for Democrats to lead the labor movement out of decline is a losing strategy.

Anna Attie, Eleanor Colbert, Ramenda Cyrus, Daniel Fernandez, Gabe Levine-Drizin and Alex Schwartz contributed research and fact-checking to this story.

This article was originally published at In These Times on May 2, 2019. Reprinted with permission.

About the Author: Jeremy Gantz is a contributing editor at In These Times. He is the editor of The Age of Inequality: Corporate America’s War on Working People (2017, Verso), and was the Web/Associate Editor of In These Times from 2008 to 2012.